The truck for prisoners stopped shortly. I heard someone speaking and then the gates opened. The prison van drove into the compound.

“Get out, here we are.”

The soldier opened the door of a ‘pocket’, a mini-compartment with one seat where it was balls-to-the-walls, and jumped out of the car and I followed. The prison van was standing in a small ‘anteroom’ between the two gates, the security building annexed on. We entered the building, where my transferral documents were passed to the chief security officer. Then I followed him to another building inside the labor camp.

“All newcomers are quarantined here,” the captain explained to me, “as a rule, the quarantine lasts for a week. My helper will now inspect you, then we’ll give you some bed sheets and you can make yourself comfortable. We won’t take the sheets from you, but you are not allowed to sleep during the day.”

When the guard officer on duty was expecting my stuff, he saw that I had a hard-smoked sausage and said, “You’re not supposed to have sausage in the forced-labor camp.” At this moment, I heard a southern accent from one of the punishment cells, “Do not give them the sausage, he’s lying! You can have it here!” I shrugged and put the sausage back into my grocery bag, which the warrant officer did not mind.

Punitive confinement consisted of five cells – three solitary cells, one mass cell for four people, and one working cell. I was escorted to a distant solitary confinement, in which I could hardly turn around when the bunk bed was down –the solitary confinement was about 2.5 m x 1.5 m and the bunk bed took up half of the room. The buzzer soon sounded, implying that it was time for all the prisoners in the punitive confinement to get up, and I heard the same southern accent.

“Hey neighbor, where are you from and what article?”

“Seventieth, from Leningrad,” I answered laconically.

“I’m from Tbilisi, also the seventieth, my name is Vakhtang, we’ll soon meet in the labor camp.”

“Cut the chatter,” a punitive confinement guard officer strictly shouted.

We did not talk anymore. The days dragged slowly by, although they brought me two books from the labor camp’s library, which I randomly asked for. A week later, they finally took me out to the labor camp and the guard officer accompanied me to a two-story stone building, where everything was located – a dormitory, a medical unit, a dining room and a common room. I was surprised that the labor camp was sunk in snow, a pile of snow reaching the second floor of the building. It seemed that they had never removed snow from there, they just cleaned the walkways and a small area for the buildings. It was late March, and there wasn’t even the smell of spring: a grey frosty day of the Northern Urals hung over the labor camp.

The guard’s officer on duty took me to the dormitory and showed me my bed.

“Make yourself comfortable, we’ll decide tomorrow what work to assign you to.”

When he left, I looked around and saw there were name plates on the beds, among which I saw some names I knew: Hleb Yakunin for example, of whom I heard over the Voice of America. Two elderly prisoners came up to me and said hello.

“Where is everybody?” I was slightly surprised.

“Everybody is working first shift, they’ll come soon,” one of them explained whilst smiling.

A fairly spacious room accommodated three rows of iron beds – two rows on one side and one row on the other. Each bed had a bedside table for personal belongings, and there was a rather narrow walkaway between the beds. I decided that I should take a look around, so I went to examine the camp, like a cat sniffing around its new home. The second floor was empty, except for a tennis table. Then there was a common room with a TV hidden in a wooden box with a lock so that it was impossible to change settings. The labor camp also had small office-like closed rooms. There was another one-story wooden building with a bathhouse, laundry room, store room for long-term storage of personal items and a shop.

“Next to nothing,” I thought, “but better than in prison. Life is livable.” This was nothing like I imagined the labor camp earlier or as Solzhenitsyn described it.

I had hardly inspected everything and settled when I heard the scamper of feet outside the barracks door (it is better to call the dormitory ‘the barracks’), the door opened and a large gray mass of people in boots, black quilted jackets and the same black trousers burst into the barracks. Their black shabby hats on their heads looked like dirty gray-black decoration, not clothing. I was sitting at my bedside table at the time and finishing sorting some things. The crowd stopped at the entrance for a moment, as if at a loss, and then almost everyone came up to me to say hello and shake my hand. I could see that they had clever intelligent eyes. When they found out who I was, where I came from and under what article I was sentenced, about ten people stayed with me and said that they would like to talk and find out the details of my case after dinner. A little later, I realized that it was a tradition at the labor camp for the “enemies of the people” sentenced for “anti-Soviet agitation and propaganda” to have a joint tea party. Each newcomer under this article was welcomed with tea and a simple “snack” of cheap chocolates and cookies sold at the local store. When we met after dinner in the smoking room, it became clear that it was no ordinary tea, but a strong drink called ‘stewed tea’. A box of tea was taken for a liter of water. If you drank one hundred grams of such “tea” you would feel as if you had drunk a nip of vodka, which greatly facilitated frank conversation. Now I was initiated into political prison and became a full-fledged member of a friendly labor camp staff.

The next day I was assigned to learning the basics of turnery and started going with everyone to the working area. It turned out to be easy and camp life took its course. I woke up at 7 a.m. and went to bed at 11 p.m. The camp was divided into three areas: a big area I was assigned to; a working area in the middle; and, a small area on the other side of the working area. One week we worked a morning shift in the working area, and the small area worked an afternoon shift, the next week we would change shifts. Most of the snow melted in May and we picked up what food we could. In the Summer it became possible to play volleyball and futsal, and we constantly played table tennis on the second floor.

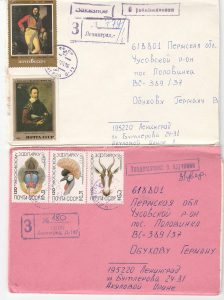

Every day I received letters from Irina and my parents, but I could only answer once a month. I was looking forward to a meeting with Irina and our marriage towards fall. I was supposed to have the first long meeting only a year after the start of my term.

On September 3rd, representatives of the District Civil Registry Office registered my marriage with Irina, after which we were allowed to hole up in a meeting room for our 3-day “honeymoon”. On our ‘date’, I got to hear all the details of the search at Irina’s apartment after my arrest. She told me that KGB officers hadn’t looked for a copy of my manuscript, but had gone straight to the linen closet where it was. Clearly they had search her apartment before my arrest and found what they wanted. The three days flew by: I even drank beer, because the guards did not know that the can with the foreign name ‘Heineken’ contained beer, not juice, as Irina stated. On October 30th, together with all the political prisoners serving their time under Article 70, I went on a one-day symbolic hunger strike in protest against the authorities’ refusal to recognize us as political prisoners. I got 10 days in a punitive confinement cell for this. On the last day of my stint (which I served in a mass cell together with a Ukrainian, an Estonian and a Georgian), we heard on the radio that Leonid Brezhnev, General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, had died. Our joy had no limits and the turnkey could not silence us. The next year of my imprisonment was far less eventful. KGB representatives from Leningrad visited me and offered me a chance to write a plea for mercy, which they assured would be granted, and I could be released after half the time. I rejected the offer as I had nothing to admit. My second meeting with Irina in the fall of 1983 was not as lyrical as the first one. Following it, I steeled myself for a long hunger and work strike, I intended to go on again on October 30th, the Day of Political Prisoners, and Irina was supposed to send a word to foreign correspondents.

It all went on as planned. Labor camp and KGB authorities were also on alert and administered me to a ward for six months. It was getting serious: the hunger strike lasted 12 days, and when I began to lose control over the situation, the camp leaders made it clear to me that they would force-feed me through a hose tomorrow if I did not end the hunger strike. A KGB officer visited me and urged me to stop my hunger strike, promising an extra short meeting with my wife, an extra package, and a transfer to a medical unit for recovery. Giving it some thought, I decided to accept the offer and end my hunger strike. My strike hadn’t achieved much anyways, and my death would shock my parents and Irina. I was immediately transferred to the medical unit with a nourishing diet, but the first few days I was recovering and did not eat much. I was on a ‘holiday’ for nearly two weeks: I got up when I wanted and didn’t have to work. The KGB officer brought a package from Irina with products prohibited for transfer to the labor camp – chocolate, caviar, hard-smoked sausage and more. Some of my friends – campmates and those sentenced under Article 70 – did not understand these developments, deciding that I had an agreement with the KGB. However, they put me back in the ward, where I weaved a wire mesh with another dissident until next May.

After my time in the ward, they returned me to the small area with a little less than 30 people serving their term. I immediately felt somewhat uncomfortable there, as I had been so used to the big area. A long meeting was postponed for six months since I had been put in the ward, and then an exile drew near. Before October 30th, a KGB officer called me in to talk and asked,

“Will you go on a hunger strike again?”

“Of course,” I assured him, “but I can change my mind if you transfer me back to the big area.”

“Okay, we will think about it,” he answered, “if you give up the hunger strike, we will settle this.”

Normally, KGB officers did not lie in such minor matters. I did not go on a hunger strike and was transferred back to the big area at the beginning of November, where I could see my friends again and meet such wonderful people as Anatoly Marchenko and Joseph Begun. It was worth it. Winter raced by in expectation of the last year of the labor camp. In July 1975, they took me to a large medical unit at the 35th labor camp, which was divided into two sections. At that time, Natan Sharansky was in the second section before being sent to the West, but I never met him. For nearly a month, they fattened me with an increased hospital diet before my transfer. I did not work, I could sleep for as long as I wanted, read books and do as I pleased.