When you’re in a labor camp, they usually transfer you without giving you prior notice. One evening, the duty officer walked in and said, “Get ready. You’ll be transferred in half an hour.” There was no point in asking where and why, you wouldn’t get any answer anyway. .

This time I was transferred back to Perm, where I ended up alone in my cell. However, I only stayed there for four days, when early in the morning I heard again, “A prison van is already here. Get ready.” I was pretty much ready already, and before I knew it, I was traveling alone with my convoy.

To my surprise, I was transferred by air this time; the flight from Perm to Sverdlovsk was rather short and they even uncuffed me when I boarded the plane. In Sverdlovsk, my escort took me to a local prison: a ‘luggage room’ they called it, explaining that the tickets to Khabarovsk were not yet available. For the first time since my imprisonment it became finally clear to me where they were transferring me. Since there were no free cells for me alone in the prison, I was going to be put in a box for those sentenced to life imprisonment or death. In fact, it was a maximum-security special box. I couldn’t really properly lie down in the cell with the bunk beds down, as the cell was less than two meters long. There was a latrine under the bunk beds and a faucet in the wall, but without a handle – you had to call the turnkey to open the water. Just like the labor camp, as soon as the door closed and the turnkey left, I heard from the neighboring cell, “Hey neighbor, what article and what term?”.

“70th, I’m being transferred to exile,” I replied.

“What article?”, my neighbor did not understand.

“Anti-Soviet Agitation and Propaganda,” I explained.

“Ahh … a politician,” the voice was clearly disappointed, “you’re getting out then.”

“Well, not really,” I did not agree and decided to inquire, “and what is your article?”

“102nd, I was given a death sentence, there’re cassation proceedings pending,” he said, and this ended our conversation.

I tormented myself in this cell for only three days, but it felt like an eternity and I could not imagine how people served a longer sentence. On the fourth morning, the food hatch opened.

“Get up and wash yourself faster. The convoy is waiting.”

I was filled with joy: finally my time in this box was coming to an end. I refused breakfast, and they didn’t give me rations as I would be transferred again by plane where they offered meals.

This time I flew in a big Tu-154, again in the front row. Like last time, they uncuffed me on the plane. When the plane took off, I took my small book for reading, which was in English. The cabin attendant noticed my book and that I was no ordinary passenger, although I was wearing a cotton pea jacket with a patch on it. She offered me an extra breakfast, but I politely refused. The plane refueled in Bratsk, so all passengers have to go to the airport terminal. I was handcuffed again, but for some reason the escort commander holding the rank of lieutenant was embarrassed that I was handcuffed and offered to cover the handcuffs with a handkerchief. I smiled and rejected the offer.

“I have nothing to be ashamed of.”

The lieutenant got even more embarrassed and did not answer. It was a long flight to Khabarovsk and we landed the next morning. The strangest things started to happen after we left the terminal: there was no prison van waiting for us and we took a regular bus. Understandably, I was handcuffed again. The bus did not reach the prison, so we walked for two blocks along a city street. It was a hot sunny day in early September, so I had taken my pea jacket off and it was carried by one of the escort officers.

They had me registered in the Khabarovsk prison rather quickly and then I was escorted to a mass cell filled with at least 30 thieves and criminals. I grabbed all the attention when I walked into the cell and stopped in the middle with a mattress and my stuff in my hands, to find a place to park myself. A young brawny fellow, around 30, with tattooed hands and all his hair cut off approached me and quietly asked, “How many did they give you?”

“Six”, I muttered shortly.

The brawny fellow, who obviously was a local leader, raised his eyebrows.

“Are you a big shot or anything?”

“Seventieth,” I gave a curt answer and added, “four years of strict-security labor camp, and now I’m being transferred to exile for another two years.”

“What article is that?” the brawny fellow was surprised.

“Anti-Soviet Agitation and Propaganda.”

“No kidding?” The brawny fellow smiled and offered his hand, “high five.”

I shook his hand and he pointed to the lower bunk bed close to the window.

“You can take this one. It’s cooler below and we’ll talk things over later.”

The whole cell curiously and cautiously listened to our conversation. When I laid my mattress and settled down, the brawny fellow called me over to talk at a big table in the middle of the cell. Two other people also joined us: these probably had the upper hand. Most of the convicts were a street gang waiting for the transfer either to a general labor camp, which was 2-3 years, or a settlement. They hadn’t had such ‘bigwigs’ yet, so I got a newfound respect.

The heat exhausted everyone – both the tough guys and the monkey boys. Many were sitting in their underwear on the upper bunk beds, covered with sweat, but their status did not allow them to go down where it was cooler. I had to spend two weeks in this company. One day at noon the officers walked into the cell, again unexpectedly, and said, “Take your belongings”. It was a different transfer: I was handcuffed to another prisoner transferred to the same place of exile as I, him for a failure to pay alimony. There was another passenger plane, though smaller – AN 24 – to Nikolayevsk-on-Amur, where we were put away in a cell for four people in a small pre-trial detention center. The heat was left behind in Khabarovsk. It was already cooler here and much more comfortable with only two people in the cell, although I would have preferred to be in a solitary one. We had spent only two days together before we were escorted again to a small city airport to board a small twin-engine L-410. Two hours of flight over the Sea of Okhotsk gave us a breathtaking view of distant snow-covered mountains and the approaching shore. Slipping over the water’s surface, the L-410 landed at a tiny airfield in Ayan village. When we got off the plane, we were ‘greeted’ by the border guards, as it was a border area. The convoy commander had not even shown the guards our documents, when I heard from the border guards’ team leader, “I take it, the other is Obuhov.”

“Yah,” I thought, “I had hardly flown in before everyone already knew and greeted me.” The border guards checked the documents and we were taken by a police car Gazik. Now I was free of a handcuffs on: there was nowhere to escape.

The escort took a return flight on the same plane, whereas the exiled alimony-dodger and I were taken by the second lieutenant to the village police station. The dirt road was along volcanic hills showing various landscapes. I felt like jumping out of the car and running away, but I had to be patient a little while longer. At the police station, they offered me a night in an open cell, which they didn’t close. Night was sinking over the volcanic hills surrounding the village, so the ‘sightseeing tour’ was rescheduled for tomorrow. It was rather cold in these parts in late September, so the district police station and preliminary detention cells were heated by a furnace. The most exciting was that we got to stoke the fire by ourselves. After I drank tea brewed on the furnace’s stove and ate a fish sandwich, we went to bed.

The following morning was sunny. The chief of district police station called me to his office, explained my rights and obligations, and then they issued an exile ID card. Before I left the district police station, the chief gave me three rubles and asked me to give them back when I received a cash transfer or my first salary.

“Where will you spend the night?” he casually asked.

“On the street if I don’t find anything,” I joked, but he didn’t understand.

“It’s already very cold at night, you’ll get frostbite. We should know where you spend the night. If you don’t find a place to stay, we’ll offer you a hostel with other exiles, although I’m sure that you won’t like it.”

Walking free with cash in my pocket, although it was still very far from real freedom, I was tempted to jump and run along the streets and volcanic hills. The first thing I had to do was to inform my parents and Irina that I had arrived and then request a money transfer and a parcel of clothes. The village post office was located in a small wooden hut near the district police station and I had to wait until the telephone operator put me through my relatives. The call office had two booths and I was the only one waiting for a call. When the phone rang, I lifted the handset and heard my mother’s voice, as if from afar.

“My boy, is that you ..?”

“Yes, it’s me, mom, hi.”

“Where are you?”

“I’m in Ayan in Khabarovsk Krai by the Sea of Okhotsk ..”

“Oh, how far have they sent you!”

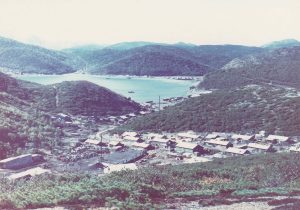

“That’s okay, this is an extremely scenic place with volcanic hills and mountains around. The village is very small, it’s a district center.”

We talked for about fifteen minutes. Irina was not at home and we agreed that tomorrow she would be waiting for my call. My mom said they would transfer me fifty rubles by telegraph that day. I had done the essentials, so now I decided to become acquainted with the village and find a place to spend the night.

“What would an intelligence officer do if he was in my place?” I thought to myself, “he would climb a volcanic hill to see the whole village at a height and see where everything was.”

That’s exactly what I did: I climbed the nearby high hill, giving a clear view of the whole village spread in the narrow hills valley. My heart was beating madly, as if I was a rabbit released from the cage after a long imprisonment. On top of this, the hill was covered with lingonberry and I flung myself on these delicious berries until I made my mouth sore. Now, having an idea of the street layout of the village, despite there only being three streets in total, I had to tramp the entire village.

It took me a couple of hours to learn everything about the village. At the end of my tour I decided to stop by a district hospital and ask whether they needed a medical equipment engineer. It was easy to find the head physician, who welcomed me.

“Are you the political one brought in yesterday?”

“Yes, how do you know?”

“The news spreads fast, especially in a village.”

“My name is Herman,” I introduced myself, “I worked as an engineer at the 1st Leningrad Medical Institute before my arrest.”

“That’s interesting,” the head physician offered his hand and we became acquainted, “let’s go to my office and talk over a cup of tea.”

We talked for about forty minutes. Unfortunately, there was neither a position nor a vacancy for a medical equipment engineer. However, the head physician offered a night in one of the empty hospital wards, to take a shower and some rest as he respected political exiles.

“Please don’t tell the police where you spent the night,” he asked, “this is discouraged here and is against the law.”

The next day, my task was to find a permanent place to stay. Walking along the street towards a hotel, I heard the creaking of brakes and a police car Gazik stopped next to me. The Major came out of the car and called to me: “Herman Viktorovich, where did you spend the night today?”

“I’m sorry, but they asked me not to tell you. Just assume I slept on the street.”

“It’s not a good idea to violate the order established for exiles starting on day one,” the Major grimaced, expressing disappointment, “you have no privileges here, although you are not a criminal.”

“I will try to check into a hotel,” I wanted to console him, “I will receive a transfer today and be able to give you three rubles back, and have enough money left for a hotel.”

“They will not check you in a hotel with your document,” the Major explained to me, “you need to get permission from the district KGB office.”

“Why?” I didn’t understand, “you’re the one giving orders here.”

“On paper, yes,” the major remarked, “but not in reality. Come to my office in an hour.”

The Major was proven right. A kind elderly woman who ran a small one-story hotel welcomed me and, upon seeing my exile ID card, said with regret: “I would be glad to check you in, but this is not allowed by the rules. You should have a passport. Contact the police, I will agree to check you in if they allow.” I had to go to the police again; they contacted the KGB office and I was allowed to temporarily stay in a hotel. One night in the hotel was cheap – 1.20 rubles. They checked me in a tiny single room, where there was space for only a bed and a nightstand. Now I was the one who locked the door.

My ‘temporary stay’ actually lasted for six months. The next step to settle in the village was to find a job. If it weren’t for Soviet laws, I could be writing my notes on the labor camp and my new book, but everyone had to work. I was sent to the village’s housing and utility services and they seemed to have been waiting for me.

“Since you have a higher education and I believe you to be an honest person, we will put a gas station under your care,” the Head of housing and utility services told me, “it’s a soft job that will take 2-3 hours a day. If someone needs gas after lunch, they will always find you and give you a lift to the gas station.”

‘Gas station’ was too strong a description. In fact, there were four huge gasoline storage tanks on the outskirts that supplied gas to the entire village. From these storage tanks, gasoline was fed through a pipeline to a small booth having a tap to control the amount of gas poured into automotive fuel tanks. Gas was self-fed under the pressure of the amount of gas in the tank, so no pump was required. There were no cars in the village exept police, KGB and CPSU party office, as there was nowhere to drive. Primarily, the vehicles that were refueled included cargo ZILs of the timber industry enterprise, although management Gazik cars also stopped by once in a while, but there were few of them. Gas was available through points and nobody was paying cash. Winter with snowstorms and snowdrifts went by fast, sometimes the blizzard lasted a day or two, and then everyone stayed home.