It will be a first-person narrative onwards

After I graduated from LETI, I got a job placement at the Gosudarswennoe Souznoe Konsruktorskoe Technologicheskoe Buro (State Union Design and Technology Bureau ) – GSKTB on my Petrograd side. I was initially pleased, but after a few months of work I arrived at a depressing conclusion – I took no interest in an engineering career.

I became keen on public life and was soon elected Deputy Secretary of GSKTB Young Communist League Committee on Foreign Relations, where I had many meetings with foreign delegates and guests. The party curator of the Young Communist League kept an eye on me for a long time and at one of the banquets they invited me to become the 3rd secretary of the Young Communist League District Committee, subject to joining the Communist Party. I had to hold back on this invitation as I was suspicious of the Soviet government. Two years later on Christmas Eve, I nearly died in a car accident and took on a new lease of life. Luckily, I was with the Military Medical Academy on duty around the city that night, and I fell into the hands of competent surgeons who immediately determined I had a ruptured spleen. I was urgently operated on and my spleen was removed.

The next morning, when I woke up in the ER, the doctor on duty came up to me and said: “It’s okay. The human body needs the spleen to grow and develop, so it’s basically useless once you turn 25”. In three weeks, following another small operation on a torn clavicular ligament, I left the clinic. The world had turned upside down. Having come to work and found out that my tourist trip to Finland and Sweden had been canceled, I said angrily to the secretary of the Young Communist League: “You’re all parasites here. I don’t want to work with you anymore”.

I quit the GSKTB and was hired as an engineer at the Research Institute for Experimental Medicine of the USSR Academy of Medical Sciences headed by academician Natalia Bekhtereva. The Institute had a more liberal attitude towards workplace discipline and political views. One evening in my apartment, my phone rang; it was my friend, who worked as a swimming coach at Leningrad State University.

“Hey! Do you feel like hanging out with some Americans? They speak Russian quite well …”

“I’m up for that, where?”

“Take a bottle of dry wine and meet us at the university pool’s sauna in an hour, we’ll be waiting for you”.

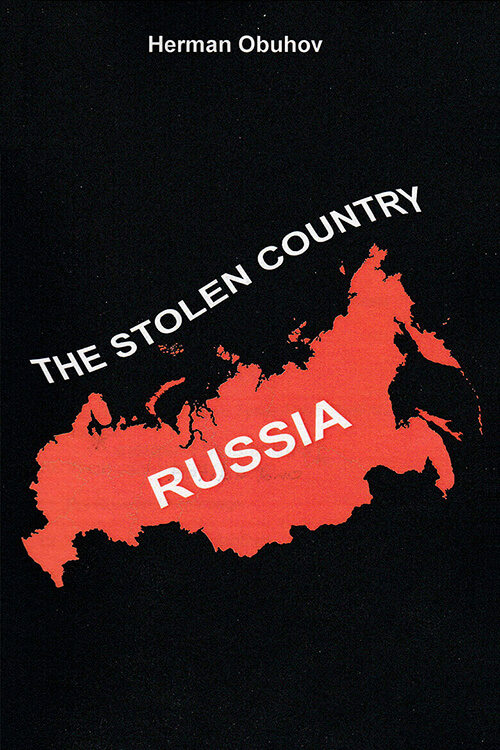

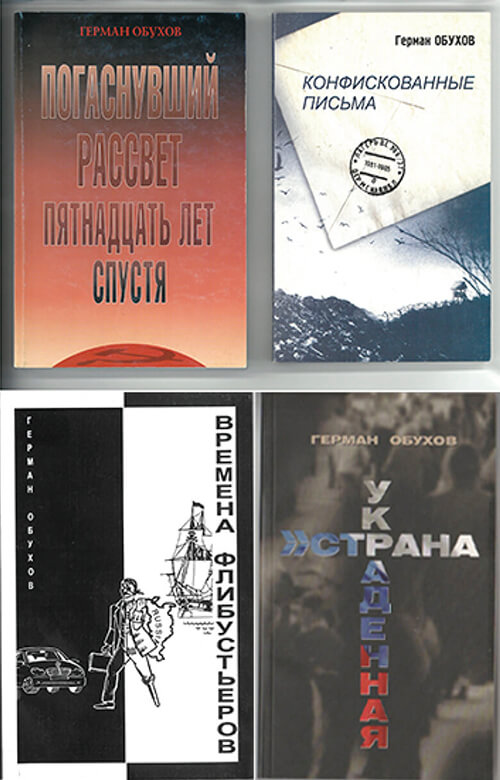

That meeting changed my life greatly. I made new friends with American undergraduate trainees studying Russian language and literature, some of whom started coming round. A year later, I got a marvelous reference at work and went to Czechoslovakia at the invitation of my philatelist friend Jan, stopping in Warsaw along the way. I became fascinated with Prague. I wanted to go further into Europe, but my Soviet passport prevented me from doing so. Having returned to Leningrad, I continued studying the foundations of Marxism-Leninism and world philosophy. I was meeting with and talking to professors at American universities. One such meeting was with Carol Luplov, a professor at Dartmouth College, and resulted in my decision to write a satirical book on the implementation of communist ideas in the Soviet Union. I called it Extinguished Dawn.

In 1979, having become financially independent with the help of my American friends who bought me rare books in Beryozka (Russian retail store) for USD to resell these books on the black market, I quit the Research Institute for Experimental Medicine of the USSR Academy of Medical Sciences and became free for a while. Book resales generated huge profits: I earned up to five hundred rubles a month, while the engineer’s salary was only 120 rubles, and resale was done once a week with wholesale buyers. The money allowed me to travel all over the European part of the Soviet Union and provided more time to write my book. At the very beginning of Autumn, I decided to go to the First Moscow International Book Fair to learn about the prospects for publishing my book abroad, as it was not realistic to publish it in my country. At the fair, I got to know Annie Chevalier, publisher of French Gallimard, and Alexander Hoffman, Vice-President of American Doubleday. We agreed that I would bring the finished manuscript to the next fair in two years and they would publish it.

After Moscow, I decided to go to Sochi on vacation stayed at Zhemchuzhina, one of Intourist’s best hotel. With decent English, I could easily get in contact with foreign tourists on the beach who bought me hard-to-find goods in Beryozka, so I successfully mixed my vacation with a little bit of business. This made my staying at the hotel cost-effective. When I returned to Leningrad, for the first time in my life I came across Soviet laws that allowed any Soviet citizen not to work for six months tops, after which you’d become a lazy freeloader. I had to get a job as soon as possible: particularly a job without strict workplace rules that would allow me to finish my satirical manuscript before my deadline. I found this exact job at the 1st Leningrad Medical Institute, where I was to arrive at work at 8 a.m. and be there all day, yet I had the only duty – to ensure that all the medical equipment in the lab functioned. That suited me just fine and I efficiently performed my duties in a few hours, and afterwards I went to the library of the Academy of Sciences of the USSR to study world philosophy and the foundations of Marxism-Leninism. It was my intention with my book to reasonably and intelligibly show the reader that communism would never be built in the USSR, it was simply a bluff. Moreover, the Soviet socialist system was built on a sham and all Soviet citizens lived in a totalitarian state without realizing it.

My friendly contacts were on the rise and I reached out to those involved in samizdat, the outlawed underground press. At one of these parties, I saw a reprinted “The Gulag Archipelago” by Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn and asked to borrow it. The owner of the book agreed, on one strict condition – not to tell anyone about this, even my relatives, and to return the book in three days. I accepted the conditions and the book greatly affected my worldview. I was certain that I had to write my own book about the deceit and deceptiveness of the totalitarian Soviet regime, but I believed it was not yet the time to talk about this with my friends. At home, I listened more and more to Voice of America, Radio Liberty, and the BBC. 1980 became the year of political confrontation between the Soviet Union and the West: in response to the invasion of Soviet troops in Afghanistan, the West boycotted the Olympic Games in Moscow. This further fueled my critical attitude towards the Soviet regime. Work on my book was progressing and at the same time I was getting to know not only Western tourists, but American diplomats and correspondents such as Craig Whitney from The New York Times. This did not go unnoticed by the KGB and I later discovered that my phone had been subsequently tapped.

In February 1981, in the Leningrad Hotel restaurant bar, I crossed paths with Irina Akulova, my future wife. When Irina came over for the first time and saw a bundle of US dollar bills on the desk left by American friends, she was shocked.

Irina was the first person I entrusted to read my unfinished manuscript, which further heightened her interest in me. She fell in love with me and I loved her back. Irina was a senior at the Polytechnic University, she was a real cutie, slim and intelligent. Since I had no money problems, we went to restaurants and bars, took taxis and dreamed that we would leave this country someday. In May, I took a short leave to travel to all the capitals of the Caucasus and Central Asia. I bought air tickets in advance and I noticed strange things started to happen, which I foolishly believed to be random. Before flying from Pulkovo to Yerevan, they unexpectedly suggested that I had an individual security check. Besides Russian rubles I had 150 bucks in my pocket and I could actually go to prison for that. When the bumbling airport workers left me alone in a small inspection room for a minute, I quickly crumpled up two 100 dollar bills and one 20 dollar bills and threw them into the trash can. The remaining 30 dollars in my pocket were not a crime. They found the money and I claimed that I’d found them on the street a week ago. The dollars were confiscated, but I was late for the plane and could only fly out the next day.

The strange occurrences continued in Yerevan. I was inspected again, this time before entering the subway. In the double room I had booked, they put in a strange young man who was constantly trying to offer me his guide services. Having toured Yerevan in two days, I left by train to Baku. In three days I took a plane from Baku to Dushanbe, then a train to Samarkand, Tashkent and Alma-Ata. I flew from Alma-Ata to Novosibirsk, visited the Science campus and returned by plane back to Leningrad. I called Irina and told her all the news from every city that I visited, having no idea that all these phone calls to my girlfriend were being tapped. I continued working on my book in the Summer, constantly meeting with Irina. I also thought of my American friends. During one of my short trips to Moscow, I secretly met in the cafe with the 3rd Secretary of the American Embassy. There was talk about the future of the Soviet Union.

“I believe the Soviet Union will fall apart before the end of this century,” as I expressed my opinion. “You’re an optimist,” the top diplomat countered. “The Soviet Union will only exist for another 50 years.”

In late August, I started to prepare for a trip to Moscow to a book fair. I even managed to buy a ticket through my friend for the Red Arrow train: these tickets did not go on regular sale, but were sold through Intourist or party structures. A few days before my departure, I came to notice quite a few strange things: there was always a Volga near my house with small antennas on the side; and, whenever I entered a shop, a man with a briefcase came right after me and didn’t buy anything. The day before departure, I agreed with my school friend, Valera, that I would come round to her house with another friend who was engaged in under-the-counter trading and was looking for sale channels. As the evening wore on, we got on a bus to take a few stops to Valera, who lived in a very uncrowded place. The Volga was driving behind our bus.

“Sergey,” I nodded my head toward the Volga, “is this your tail?”

“Who’s interested in me? I deal with little guys, and these must be KGB officers, they wouldn’t waste their time on me.” Sergey grinned, “You’re the one meeting with all kinds of correspondents and diplomats, it’s you who’s being tailed. In any case, we shouldn’t bring the tail to your friend. Let’s get off one stop sooner and see what they’ll do”.

That’s what we did. There was no one around. As soon as we got off the bus, the nose of that same Volga came into view round the bend. We flitted down the street opposite Valera’s house. The street was barely lit and we saw a small square on the way.

“Let’s turn here,” Sergey plucked my sleeve. We stood in the thick and tall bushes of lilac. A few minutes later, two men ran by clearly chasing someone.

“Let’s get out of here through the back yards, they’ll be back soon,” Sergey took me by the elbow. We kept running and made sure there was no tail behind us. Then we made it to Valera’s house.