After a very long journey along the directorate hallways accompanied by the warden, he remarked,

“You should keep your hands behind your back when we go to the pre-trial detention center or from there to the directorate.”

I ended up in the pre-trial detention center. I started off by being searched: they took my staff and my bag for storage, and even forced me to hand over my shoelaces. “Idiots”, I thought. The same warden led me into the cell, first stopping by the back room, where they gave me a mattress and a set of bed linen.

“We will bring you dinner soon,” the warden informed me.

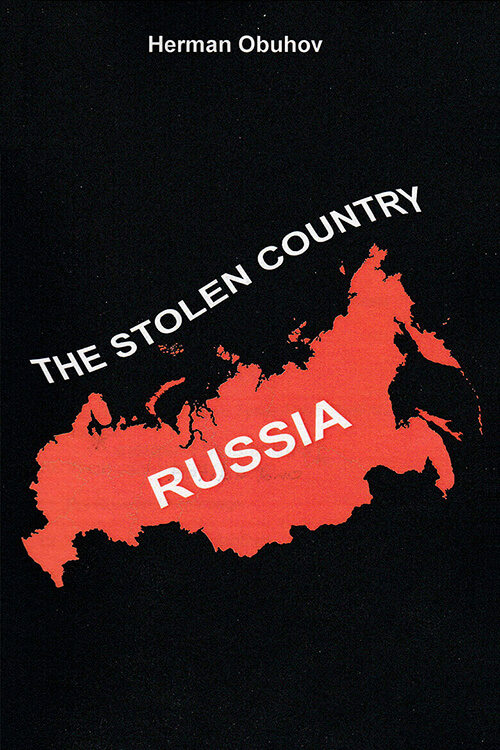

“Thank you, keep it. I have already been fed,” I replied. When the cell door closed behind me, I looked around this “exotic place to sleep” and thought to myself, “I could not even dream of it. The KGB covert operation to detain a particularly dangerous USSR state criminal, who wanted to transfer his manuscript to the West for publication, containing no state secrets, was completed successfully. All those involved in this covert operation no doubt received awards and obtained higher ranks.”

The next morning, I was roused by the buzz of the KGB pre-trial detention center. Moments later, the food hatch opened and the puffy face of the warden appeared through it.

“Get up, there will be breakfast soon.”

“Thank you, I’ll manage without breakfast,” I said, but I had a feeling that they would not let me sleep. So I got up, washed myself and prepared for a new life. I refused breakfast and laid down on a made-up bed. I remembered my life in the army, that experience was now useful. They took my watch so I could only guess the time, which hung heavy since there was absolutely nothing to do. I was laying on the bed and looked at the ceiling. After a while, the door bolt rattled and the key turned, the foreman from the detention center’s guard appeared in the doorway.

“Get up. They are calling you in for an interrogation.”

Another walk along the long hallways. At the end, the warden opened the door to a different room. There was a different KGB officer out of uniform sitting at the table, he was not the one I talked to yesterday. He motions to the next empty table and chair.

“Have a seat, Herman Viktorovich. We’re going to have a long conversation. You shouldn’t have refused the breakfast, it would not help at all.”

After a short pause, he added, “My last name is Isaev, I’m a Major of the KGB. I was sent to law enforcement by my factory’s management, where I worked as an engineer. I have the same education in technical fields as you do. So we should be able to find common ground. I’d like to offer you tea and a ham sandwich to make you feel, pardon the pun, at home.”

“Well, well,” I thought, “velvet paws hide sharp claws.. We have different ways, Engineer Major Isaev.” Not waiting for my answer, the major turned on the electric kettle and took a plate with a sandwich from the shelf of a massive bookcase.

A few minutes later the kettle boiled and the Major brewed a pinch of Indian tea in a faceted glass with a glass holder, scooping the tea from a box with a small spoon. He put the glass of tea and the plate with the sandwich on the table in front of me and took his seat. I watched this act of ‘hospitality’ with a slight irony and did not fail to be malicious.

“Is there anything in this tea?”

“What you mean?” the Major was surprised.

“I don’t know,” I wanted to make him sit up, “and what was in the tea in the train?”

“What do you think was in there?” The Major was even more surprised.

“That’s what I would like to know, since I didn’t feel well after that tea and it triggered my arrest by your agents,” I had to explain.

“That was all your imagination,” the Major brushed off. “Our agents were not there.”

There was no point in arguing with him, or in giving up tea and a sandwich, since I was on a new stage of life now and my resistance to the huge repressive apparatus of a totalitarian state had begun, and this required strength. The Major waited till I finished my light meal and continued, putting a piece of paper in front of me.

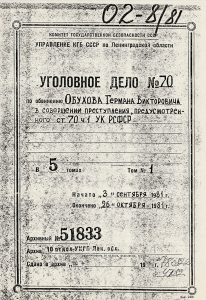

“This is the order from the prosecutor to arrest you and keep you in custody until the end of the investigation and trial.”

“No wonder this is your prosecutor,” I really wanted to piss him off. “This is a Soviet prosecutor acting under the your law.”

The Major undisturbedly reacted, “And you must know that we found all copies of your libel.” He slightly raised two open packages on his desk. This was the most unpleasant and painful news for me.

“Bastards,” I thought, “you managed to find them, three years of work gone up in smoke.” These findings upset me much more than the arrest and being in this building, but I did not miss a beat. “How did they find them?” I continued to ponder, “it’s clear how they found a copy at my place, but how did they manage to find Irina’s copy?”

“If you make a confession,” the Major said, “it will commute your sentence.”

“Confession to what?”

“To making and storing the libel you intended to publish abroad, thereby damaging the prestige of our country and the Communist Party.”

“Firstly, this is not a libel, but a manuscript, and secondly, would the Soviet regime have collapsed after this publication?”

“It would not have collapsed,” the Major calmly retorted, “but it would have suffered great damage. We qualify this as anti-Soviet agitation and propaganda according to Article 70 of the Criminal Code of the RSFSR.”

“I wonder who did I agitate?”

“That is what we have to find out,” the Major concluded.

“There is nothing to find out. I wrote this and so what? Our Constitution states that we have freedom of speech.”

“Yes, but it does not states that your freedom continues after that speech,” the Major joked, “After lunch you will be fingerprinted and photographed. This is required when initiating a criminal case.”

“I don’t get it why it’s impossible to immediately draw the line and close the case with my confession that this is my manuscript?”

“That’s not how we work,” the Major retorted. “We should conduct expert examinations, find out all the causes of the crime, reliably establish your implication in a crime , your application will be officially registered, but what if you confess to untruths?”

Things were set in motion. The next day I was transferred to another cell, where there was another person under investigation, who, as I later found out, was merely there to find out about my contacts on the outside. Since I did not have any underground organization and there were no such contacts, it all turned out to be lost KGB labor. Every day, except Saturday and Sunday, I had to go to interrogations, where I was asked stupid questions. What could be done in a week was extended to over two months. My daily routine consisted of the following: waking up at 6 o’clock in the morning; breakfast; a walk in a small courtyard with an observation tower; interrogations, lunch; and more interrogations. I underwent a psychological examination, which confirmed my common sense; a handwriting examination, which recognized my amendments to the manuscript; and, other examinations which proved useless to the KGB. Finally, everything was ready for a show trial and I was taken to Leningrad city court. On the first day, the judge read out the indictment – the KGB officers had composed three whole volumes. On the second day of the trial, on my birthday no less, they pronounced my sentence. In addition to my parents and Irina, there were several strangers in the hall, obviously KGB personnel, to build up a false atmosphere of an open hearing. My last word was short and specific – I did not admit either my guilt or the intent of agitation, however, I did not deny authorship. After the judge pronounced the sentence to four years of strict-security camps and two years of exile, I wanted to laugh, but Irina burst into tears. I had to cheer her up, so I waved at her and made a V (victory) gesture with my fingers, much to the displeasure of the guards. Our honeymoon trip to Odessa was delayed for six years.

On the next day of the trial, I was transferred to another cell with another convict, whose name was Boris. We became acquainted and it turned out that he was sentenced to three years of camps with no exile, under Article 70 Anti-Soviet Agitation and Propaganda for writing some poems.

“My manuscript was real scheming against this system, but poetry?” I thought to myself.

Boris and I quickly became friends. During our time in the open air, he read me his poems, and I read him the excerpts from my manuscript. A month later, he was taken to a labor camp, and I was left to wait for a response from the Supreme Court to my appeal against the sentence, although there was practically no chance of changing anything. When Boris had gone, my new cellmates were fighters against corruption, smugglers and defectoe abroad. They had one thing in common: they did not do any harm to the Soviet system. The smuggler brought from abroad something that was unavailable in the USSR and he bought it for his salary; the defectoe abroad from the Soviet Union just wanted to go to the West, but they didn’t let him, the corruption-fighter handed out flyers in the subway. Who did the KGB fight with? The answer was obvious: they fought with those who wanted to change their life or the life of the country for the better.