The Aeroflot plane was taking me to the unknown and I was not only crossing the state border, I was crossing the border between two worlds. Putting my foot on English land at Heathrow Airport, I went to the border control and showed my exit visa to an immigration officer.

Puzzled, he took my visa and studied it carefully; he held it up to the light and did not understand a thing. He asked me to wait. Fifteen minutes later, his superior came out and asked,

“Who invited you?”

“Amnesty International”

“Please wait a minute.” He came back in another five minutes and stamped the entry date in my visa and said,

“Welcome to Great Britain.”

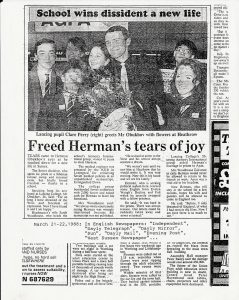

When I walked in the lounge, I could not believe my eyes: there were at least fifty people with flowers and posters, BBC and Associated Press reporters waiting to greet me. We had a ten-minute photo shoot, then a talk at the airport restaurant, and then a whole motorcade and press cortege moved me to Lancing College, where I had arranged it all. Over the next two or three days, all the UK newspapers, including The Times, published stories about my arrival. When we arrived at Lancing College, I had an interview with the BBC on-site team, who made a short film against the backdrop of one of the oldest and most prestigious colleges in England.

After that, there was a sort of banquet in the house I was staying, of James Woodhouse, College President, and his wife Sarah. The next week, I was exploring the city, other colleges and universities, where I was talking about pressures against dissent in the Soviet Union. Then my new friends, whose children went to this college and had sent parcels to my family in Leningrad, invited me to stay for a while in their house and loaned me with their apartment in London for the period of my stay in the capital. I made a trip to Cambridge to meet Vladimir Bukovsky, who had invited me over having heard about my arrival on TV. During my first days in London, I visited the US Embassy in Great Britain and found out that America had an open-door policy: back in 1985, the US Congress had passed a law according to which all political prisoners of the Soviet Union were granted political asylum in advance – they only needed to contact any US embassy outside the USSR. Once I stated my willingness to be granted asylum in the United States, they started preparing for my departure to Frankfurt am Mein in Germany, where they drew up the documents for all political refugees from the Warsaw Pact countries.

About a week after I moved from Lancing to London, two strong men buzzed my townhouse door. They claimed to be MI6 Colonels and offered to talk at a nearby restaurant. I was speechless when they asked the owner of the Japanese restaurant to close the doors for a short time so that we could talk privately. Japanese cuisine was completely new to me, so I could not say what I would prefer to order from 40 dishes. Therefore, they decided to order the entire menu in small portions.

“I won’t be able to eat that much!” I tried to protest.

“That’s okay, you can try whatever you want.” The Colonels demonstrated they were well aware of Soviet realities and a number of secrets. At the end of our conversation, they left me their phone number.

“If you happen to decide to work with us, give us a call.”

I didn’t dare to. Slightly sad, I said goodbye to my new Lancing and London friends in mid-May.